The story of botany at Magdalen is very much intertwined with the teaching of botany at the University, stemming primarily from the links between Magdalen and the Oxford Botanic Garden, the oldest surviving Botanic Garden in Britain. In the early 17th century, Henry Danvers, 1st Earl of Danby, decided to give money to the University to create a Physic Garden (later called the Botanic Garden), as a place to grow medicinal plants.

Detail of a 1732 engraving based off of the 1578 map of Oxford by Ralph Agas. Bodleian Libraries Gough Maps Oxfordshire 4. The location of the Physic Garden is in the empty fields at the top left of the map.

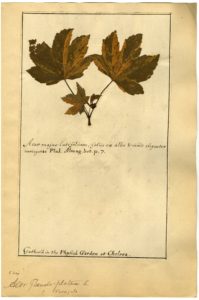

Acer pseudoplatanus, 1676, the original plant is likely to have been collected from Magdalen College Grove. Oxford University Herbaria, Department of Plant Sciences Dubois Acer 1493

The place chosen for the Garden was on the banks of the River Cherwell in land owned by Magdalen College; in April 1621, Danvers paid the lease to establish the Garden. The land was raised above the flood plain, walls were built of local limestone from Headington, and plants were sourced from the leading gardeners of the day including John Tradescant the Elder (gardener to King Charles I). The Garden employed its first superintendent, Jacob Bobart the Elder, in 1642 and he was succeeded by his son Jacob Bobart the Younger. The Bobart’s diversified the plant collections and produced detailed records of the plants present – both in the forms of catalogues and herbaria. Herbaria are records of pressed plants used for the description and taxonomic identification of species. These early herbaria were the start of what was to become the Oxford University Herbaria which now contains approximately 1 million specimens, an invaluable resource of examples of plants from across the world.

Detail of David Loggan’s map of Oxford from his Nova & accuratissima celeberrimæ universitatis civitatisque Oxoniensis Scenographia (1675) Bodleian Libraries (

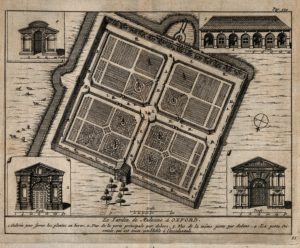

Botanic Gardens, Oxford: plan of the gardens with details of the gateway and greenhouses. Etching, 1707, after D. Loggan. Wellcome Collection

These early herbarium sheets also provide a unique window onto the plants that were growing in the 17th century across the road from Magdalen, and include both of the floral icons of the College, the Madonna lily and fritillaries. The Garden maintained a close link with Magdalen and even contained plants collected in the College. Furthermore, the first superintendent, Bobart the Elder, was also the landlord of the Greyhound Inn– a pub on Magdalen land on the site that is now the Longwall Library. Even in its early state the Garden attracted some famous visitors such as the Prince of Orange, future King William III, and Samuel Pepys, visiting the Garden in 1668, who famously thought of Oxford as a “mighty fine place.”

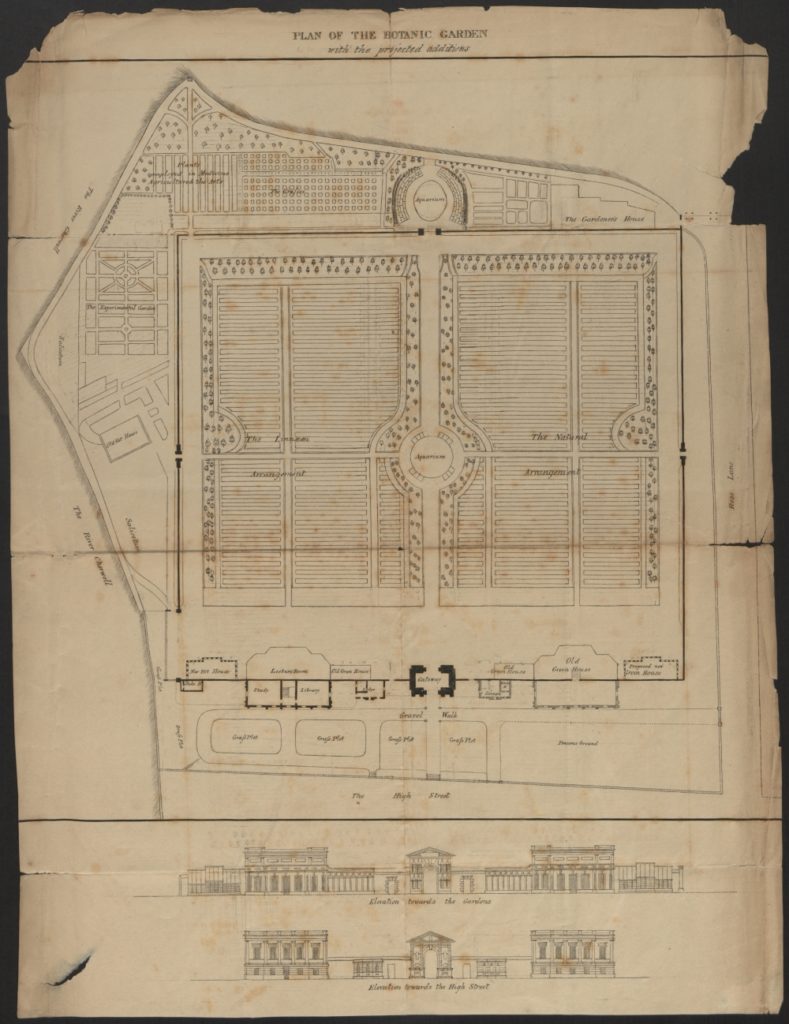

19th century plan of the Botanic Gardens with the projected additions Elevation towards the Gardens Elevation towards the High Street. Oxford History of Science Museum, 14105

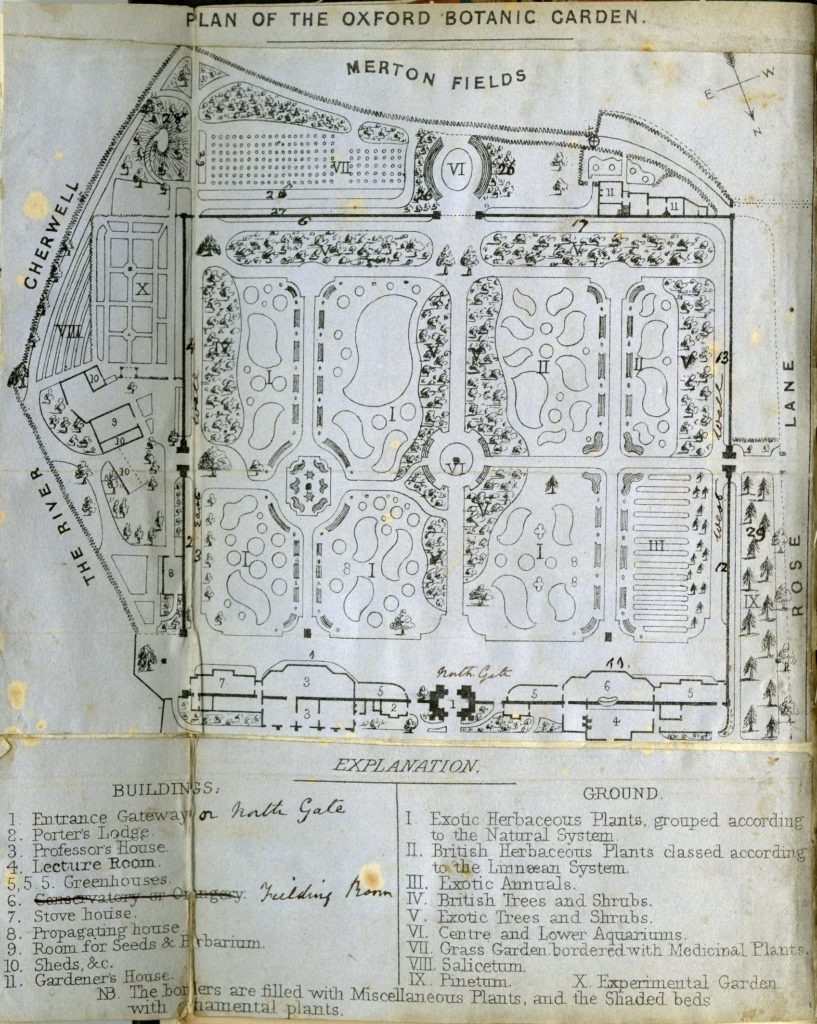

19th century plans for redesign of the grounds of the Botanic Garden. Sherardian Library of Plant Taxonomy MS Sherard 265a f.iv(v)

The Botanic Garden became the centre for teaching botany in Oxford with the first Professor of Botany at Oxford University, Robert Morison appointed in 1669 giving his lectures there. The link between botany at the University, Magdalen and the Garden was cemented further in the 18th century with the endowment of the Sherardian Chair of Botany by William Sherard, which to this day pays for a Professor of Botany at Magdalen College.

One of the most important Sherardian Professors of Botany was Charles G. B. Daubeny (1795-1867). He played a key role in Magdalen as both Bursar and Vice President and was influential within the University as a strong promoter of science. He also implemented a number of important changes to the Botanic Garden when he became Sherardian Professors of Botany in 1834. He raised money to redesign the Garden, he built new teaching and research spaces, and built new glass houses featuring a hot water tank and endeavoured to make the Garden more welcoming to the public. He also realised that the then called “Physic Garden” had surpassed its name and grew far more than medicinal plants so in his first year as Sherardian Professor of Botany he changed its name to the “Botanic Garden”.

The lasting influence of Daubeny’s work was closer links between Magdalen, the Botanic Garden and teaching at Oxford with all botany taught in the buildings by the Garden until 1951. Even though botany (now the Department of Plant Sciences) moved to the Science area on South Parks Road in the 1950’s, the links between the College, the Department, and the Garden continue to grow. The floral icons of Magdalen, the Madonna lily and fritillaries, are still grown as they were in the 17th century at the Garden. Daubeny’s legacy continues – his 19th century laboratory was recently refurbished as a new Lecture Theatre and students still take practical classes at the Botanic Garden.

The link between Magdalen College, the Botanic Garden and the teaching of botany at the University was further strengthened in the 18th century with the endowment of the Sherardian Chair of Botany by William Sherard. The first Sherardian Professor of Botany was Johann Jacob Dillenius appointed in 1734 and the current Professor, Liam Dolan, took up the post 275 years later in 2009.

Fifteen individuals have held the Sherardian Chair, working on a wide diversity of botanical topics. However, a common theme amongst the chair-holders has always been promoting botany in College, at the University, and on an international stage. The early Sherardian Professors in the 18th century were instrumental in establishing the Oxford University Herbaria. In the 19th century, Charles Daubeny stood out as a pioneer, most noticeable for his redevelopment of the Botanic Garden and the building of new teaching and laboratory space in the now-called Daubeny laboratory. At the end of 19th and beginning of the 20th century three Sherardian Professors, Isaac B. Balfour (who held the chair between 1884-1888), Sydney H. Vines (1888-1919) and later Arthur Tansley (1927-1937) played central roles in promoting the scientific publication of botany. Isaac B. Balfour, translated key botanical texts on anatomy, morphology, pathology and physiology from German to English, making the works of the great German school of botany accessible to an English speaking audience. Sydney H. Vines and Balfour, with other leading botanists of the day (including Francis Darwin – Charles Darwin’s son), founded the The Annals of Botany in 1887, the oldest continuously published botanical journal. Later Sir Arther Tansley founded the New Phytologist in 1902 and served as its editor during his Sherardian Professorship.

Today both New Phytologist and The Annals of Botany and are still key journals reporting plant sciences research and both maintain links with Magdalen, through the current Sherardian Professor Liam Dolan and his predecessor Hugh Dickinson. During the 20th and 21st century the research of the Sherardian Professors has hugely diversified, spanning ecology and biochemistry to genetics; however much of the research still has links to the work of their early predecessors. Although over 275 years have passed between Dillenius and Dolan the two share common ground: one of Dillenius’s most important works was the publication in 1741 of Historia muscorum (the natural history of mosses). Today, Professor Dolan’s work is still focused on mosses, liverworts and clubmosses featured in Dillenius’s book, but technology now allows their description using the genetic basis of their natural history.